History of King’s Cross

The story of King’s Cross begins with the Fleet River and a small settlement, which grew up at a place known as Battle Bridge, named after an ancient crossing of the Fleet River which flows beneath, near the northern end of present-day Gray’s Inn Road.

Some of the earliest enterprises in the area were the spas, which developed around the Fleet’s springs, becoming fashionable resorts in the eighteenth century. It was, however, an early attempt at traffic planning which determined the area’s fate. Thomas Coram built the Foundling Hospital for children in 1742-1747 just south of the present day King’s Cross and ten years later, in 1756, the New Road was cut across the fields from east to west to channel traffic away from the city centre. Today, as the ever-busy Euston Road, it serves the same purpose.

By the early-nineteenth century Battle Bridge had become a depressing place. It was low lying and subject to flooding. The Smallpox Hospital had been built in 1769 and a fever hospital was added in 1802. It had become notorious for its tile kilns, rubbish tips and noxious trades. The Regent’s Canal, opened in 1820, attracted other industries such as gas works. A rescue attempt was made in 1829. How different it could have been if the Panarmonion project, offering recreational and cultural activities, had been a success. It’s failure led to the site being developed for housing, leaving only Argyle Square as open space. Associated with the plan was a statue of King George IV built in the middle of the road junction. It gave the area a new name – King’s Cross.

Railways

To most people the area is synonymous with the station. The arrival of King’s Cross Station in 1852 followed by St Pancras in 1868 had an enormous impact, establishing it as an entry point to London for visitors, immigrants and goods from the north. The construction of the Underground lines confirmed it as a major interchange. For the people who lived in King’s Cross these developments were a mixed blessing, providing work but also great upheaval. he expansion of land taken for railway use involved the demolition of whole streets of what were generally considered as slums, but many lost their homes and this added to overcrowding in the small terraced houses to the south of Euston Road. Model housing blocks such as Stanley Buildings, Derby Buildings, the late-Victorian flats of the Hillview Estate and more recent council flats are examples of projects to provide the district with good, affordable housing.

Still surviving today, however, is St Pancras Old Church. It is named after Saint Pancras, a fourteen year old boy beheaded in Rome in 304 for his faith. A church was founded on this spot some years later making it quite possibly one of the oldest Christian sites in Britain. It stands in St Pancras Gardens, the former burial grounds of both St Pancras and St Giles in the Fields parishes. The coroner’s court, built in 1881, was erected on a piece of ground used for the reburial of the remains of closely packed decomposing bodies which had been exhumed during Midland Railway’s approach works to St Pancras Station in 1866.

Once the fortunes of King’s Cross were linked to that of the railway industry, it also suffered from its problems. After surviving Second World War bombing the railways succumbed to post–war decline, particularly in goods traffic. Vast areas of sidings and warehouses became redundant and turned to wasteland; by 1955 the area was suitably run-down, a seedy backdrop for the Ealing comedy ‘The Ladykillers’ starring Alec Guinness released the same year. A low point was reached in 1966 when a plan was put forward to amalgamate the two termini, which would have meant the demolition of St Pancras Station. Since then a number of redevelopment schemes have come to nothing.

King’s Cross has suffered from years of neglect. It is noisy and chaotic yet visitors and residents look upon it with affection. It has some success stories. Camley Street Natural Park beside the Regent’s Canal provides a welcome green refuge. Euston Road is home to Camden Town Hall; the administrative centre of the borough, and opposite is the prestigious new British Library. Next door, St Pancras Chambers is being restored. Since 2007 Eurostar Trains has provided a link with Europe and in 2012 there will be a shuttle link with the Olympic site at Stratford. Meanwhile, with the development of 67 acres of disused goods yards, there is no doubt that this will once again bring enormous change to King’s Cross.

SOURCE: http://camden.gov.uk/ccm/content/leisure/local-history/kings-cross-voices.en?page=

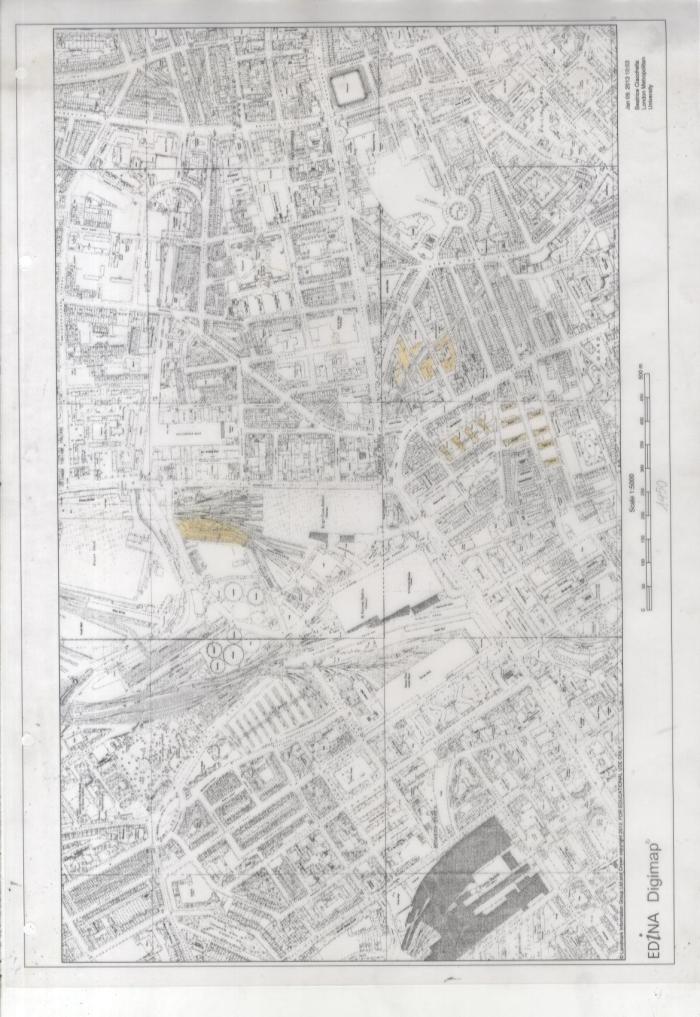

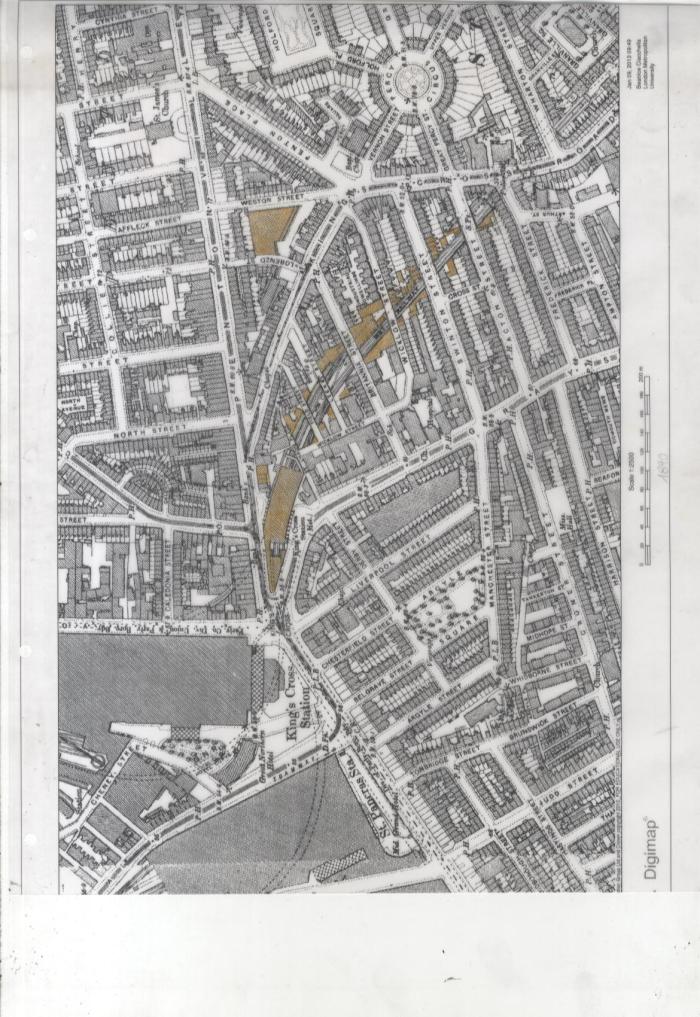

Historic plans of the Kings cross area in scale 1:5000

kx 1870 The stations have just opened at this point, but the industry around them hasn’t developed quiteyet, leaving the site being characterized by housing.

1910 – By now the stations have become a major entry point to London forpeople and goods arriving from the Midlands and the northern part of the UK. The main role aquired by the stations led to the need of more land, therefore areas covered by ‘slums’ were demolished and converted into coal deposits, goods sheds and other functional spaces for the rail industry.

1950 – During Second World War, as focal point of the city, both the stations of Kings Cross and Saint Pancras were subject to bombing, together with the whole surrounding areas. It is in these areas that is possible to see how the bombing influenced the pattern of post war social housing.

Bombed areas in Kings Cross ( the bombs hitting the stations havn’t been mapped for security reason)

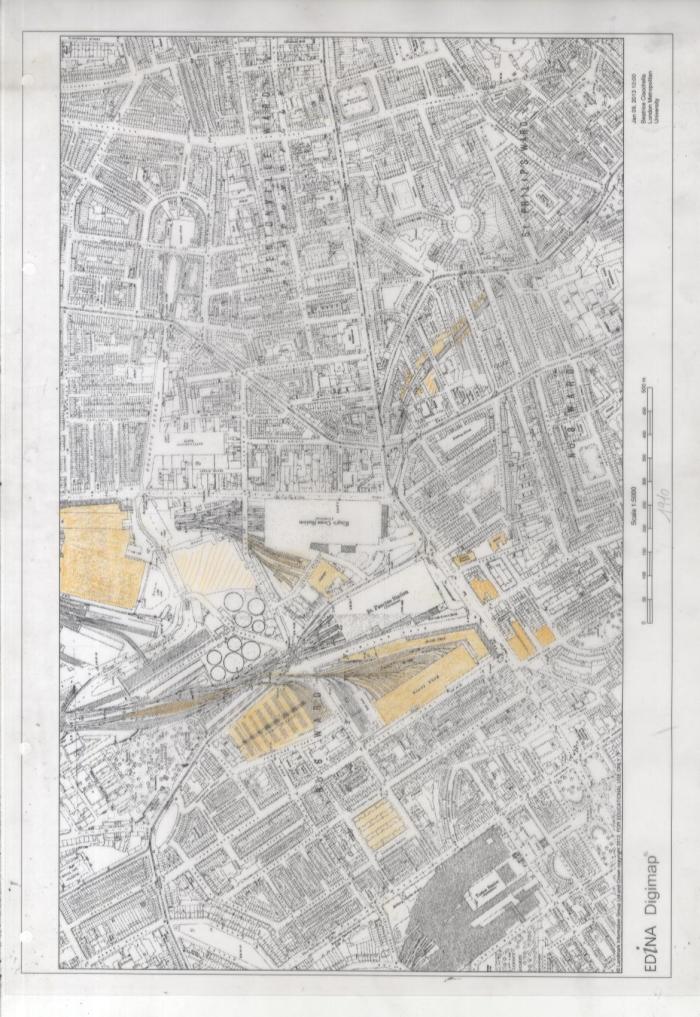

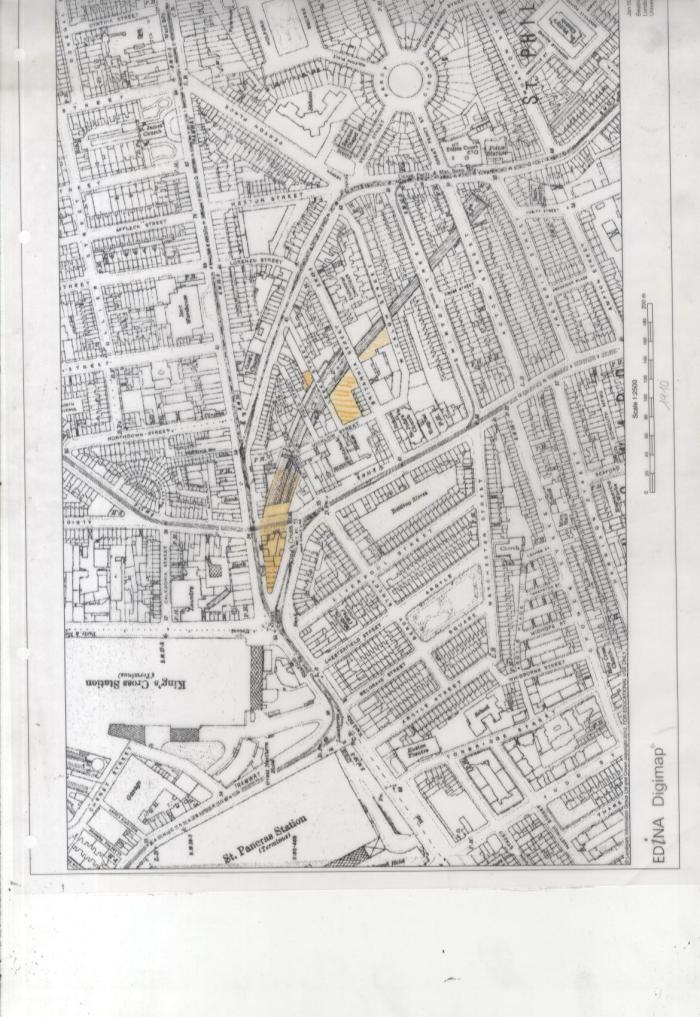

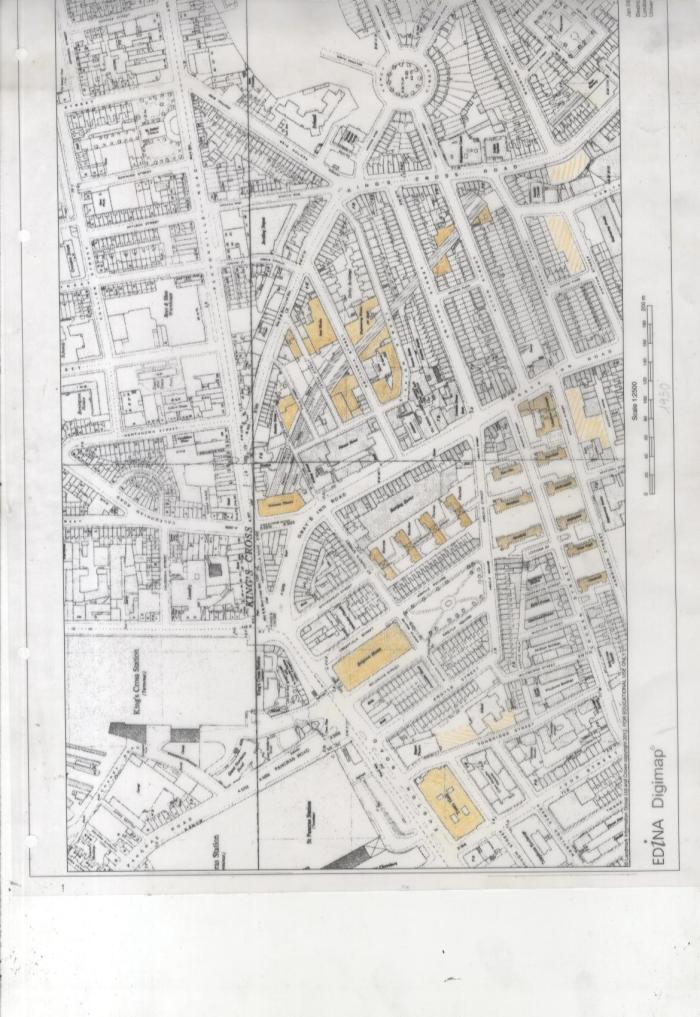

Historic plans of site in scale 1:2500

site 1870 The stations have just opened at this point, but the industry around them hasn’t developed quiteyet, leaving the site being characterized by housing.

1890 – It is possible to notice how the new rail system has started having an impact onthe area, as the Underground Station just on the south side of Pentonville rd. has been enclosed, due to the increased use of this. The areas along the trackscrossing the site, left empty as considered not right as a living environment, have now been exploited to construct more housing, but mainly deposits related to the rail industry.

1910 – The increasing traffic in this area led to some change in the roads system like the one that sees the opening of a new road, creating a new junction passing over the old underground station, and leaving on one side, space for new developments of small commercial activities/ housing.

1950 – After the bombing of the second World War theres a boom in the social housing clearly visible also in the south area of kings cross. Around the site’s tracks bigger complex of buildings have buin built, facing directly onto the tracks.

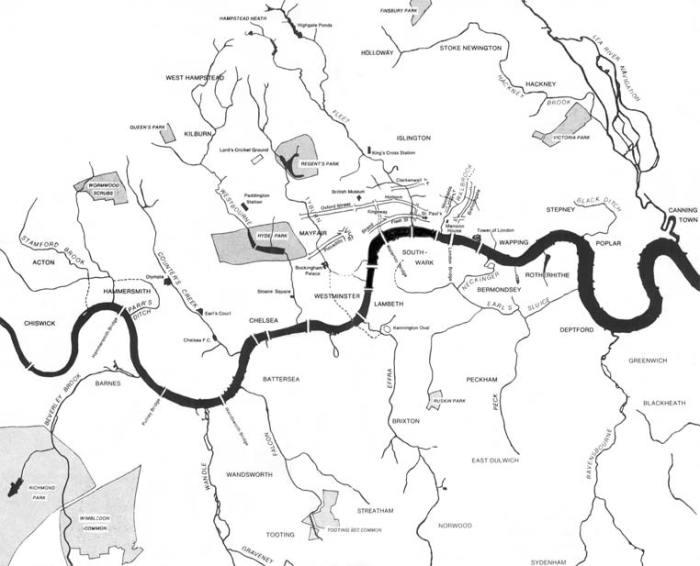

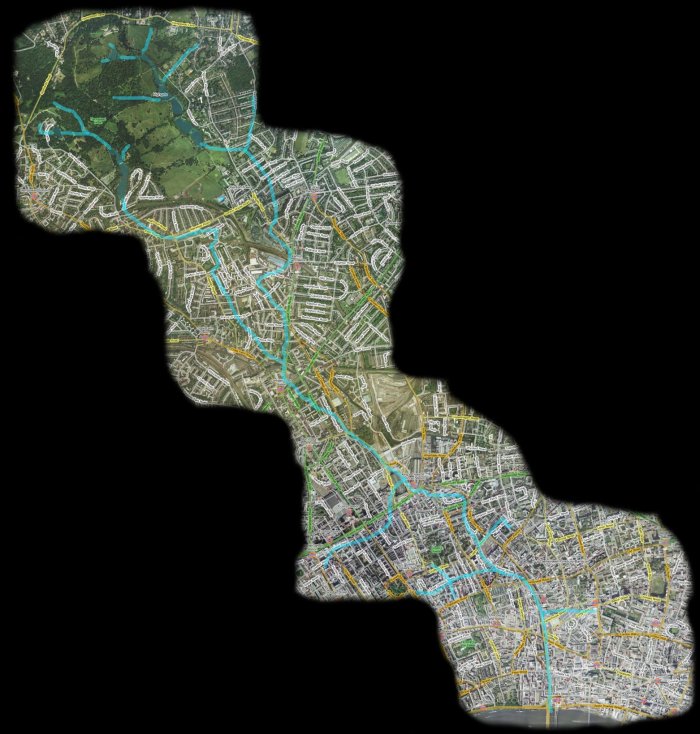

The fleet river, once crossing the river of Kings Cross has both been cause of its fluorishing around the 1700 but also of its depression, making it subject to several floods.

Here is two images one showing all the lost rivers of London and another one more specific showing the fleet river from its source to the meeting with the Thames.

The Development on Kings Cross

The railway lands comprises some 135 acres extending from the north London line at the north of the site to the two major railway stations of kings cross and St. Pancras at the southern end of the site.

The area was largely established by the end of the 19th century and contains the best group of early Victorian railway building in the London area. The historical significance of the area has been recognized through the listing of the some of the buildings, including the railway stations and the declaration of the conversation areas that cover most of the southern part of the site.

The railway lands are principally owned by British Rail, the National Freight Corporation, the British Waterways Board and North Thames gas. Blight has resulted from uncertainty over future plans for the area and it now has a generally run down appearance. There are large tracts of vacant land in the goods yard and many building are under-used. The northern part of the site is used for importing aggregates by rail for processing into concrete, which is then distributed by road to building sites in central London. Many small and a few relative large businesses on generally short leases occupy other part of the site.

Surrounding the site are the residential communities of Somers town and elm village to the west, maiden lane to the north, thorn hill to the east and kings cross to the south. The small residential community within the site is concentrated in and around Stanley building/Culross house. The new British library development is adjacent to the south west corner of the site and euston road, with its commercial and office developments including Camden town hall, borders on the s6touthern end of the site

The existing train sheds of St. pancreas and kings cross are clearly visible form surround areas and are a major element in the strategic views south from parliament hill and primrose hill. The canal and the gas holders are other familiar landmarks which contribute to the character of the area as is the more recent development of the Camley street Natural park, based beside the canal and how viewed as an essential element in any long term proposals for the site. Despite the run down appearance, there is much of interest in the buildings and the activities of the site.

The Regent’s Canal:

The Regent’s Canal was authorized by an act of 1812 and after financial problems, its was completed in 1820. This canal connected the Grand Junction canal at Paddington to the Thames at limehouse skirting the then built up area and falling 100ft by 13 locks in 8 miles. Water supply was always a problem, until amalgamation with the Grand Junction canal in 1926, and back pumping from the Thames was introduced in the later 19th century. The cottage at St. Pancras locks is converted rom a back pumping station of 1896. Maiden lane Canal Bridge retained by the GNR was rebuilt in 1850 in cast iron and remains in that state though widened.

The London and north western, the great northern and the midland railway all had interchange facilities with the canal, and much traffic was distributed thereby to waterside premises, including the docks. Coal, particularly for gas and electricity works, was transferred from rail at the St. Pancras and kings cross coal basins, successfully competing with sea-borne coal. Other important traffics on the canal were softwood timber imported through the docks; bricks from the canal and riverside brickfields and return load of manure and town refuse. A former cattlefood mill is the survivor of several grain mills and warehouses in the vicinity of the goods station. Battle bridge basin is one of several arms along the canal that were surrounded by wharves and factories. Commercial traffic continued on the canal until the 1960’s. In the mid 1970’s the second of each pair of lock chambers was converted to a floor weir, so permitting the de-manning of the locks and freer access for the public.

Kings Cross Railwaylands by Michael Parkes